Why do large quantitative analytics platforms fail?

The unsatisfying but honest answer is: it depends. There is rarely a single root cause. Platforms almost never collapse because of one flawed model, one architectural mistake, or a single ill-judged rewrite.

Most platforms do not break suddenly. They slowly lose coherence.

They continue to run, produce numbers, and deliver outputs, yet over time the relationship between assumptions, inputs, and results becomes increasingly difficult to explain. Understanding this distinction matters. There is a difference between a system that stops working and a system that no longer makes sense.

This post is not an attempt to produce a definitive list of failure modes. Instead, it aims to frame how platform failure tends to emerge in practice, based on repeated rebuilds across banks and hedge funds, often long after the original design decisions were made.

Architecture as the Management of Structural Tensions

Large analytics platforms are not defined by the sophistication of their models or the elegance of their code. They are defined by the set of structural tensions they are expected to hold.

Every non-trivial platform sits at the intersection of competing objectives: accuracy versus performance, flexibility versus stability, reuse versus specialisation, short-term delivery versus long-term coherence. None of these tensions are pathological. They are inherent.

Architecture, in this sense, is not a static blueprint. It is the ongoing discipline of making tensions explicit, choosing where to land, and enforcing those choices consistently over time.

Platforms rarely fail because they chose the “wrong” side of a trade-off. They fail because trade-offs were never made explicit, or because different parts of the organisation made them implicitly, in different ways, and at different times.

A Canonical Fault Line: Flow and Exotics on a Single Platform

One place where this loss of coherence becomes particularly visible is when a single analytics platform is expected to serve both Flow and Exotics trading businesses.

This is entirely viable. Many organisations attempt it, and some do it well. But it requires a clear understanding of the fundamentally different objectives involved.

Flow businesses typically optimise for throughput, predictability, and operational stability. Latency, control, and repeatability matter. Exotics businesses, by contrast, prioritise modelling richness, scenario exploration, path dependency, and structural nuance. Higher computational cost is accepted in exchange for expressiveness.

The failure mode is not unification. The failure mode is unexamined unification.

Too often, differences in basis, modelling assumptions, and market data are hidden rather than engineered. Abstraction is used to smooth over genuine divergence instead of building deliberate bridges to manage it. When this happens, the platform does not become simpler. It becomes ambiguous.

That ambiguity rarely surfaces immediately. It emerges later, under stress, and often far from its point of origin.

How Unresolved Tensions Accumulate in Practice

In practice, platform failure does not announce itself. It emerges through the gradual accumulation of unresolved design tensions, each locally reasonable, collectively corrosive.

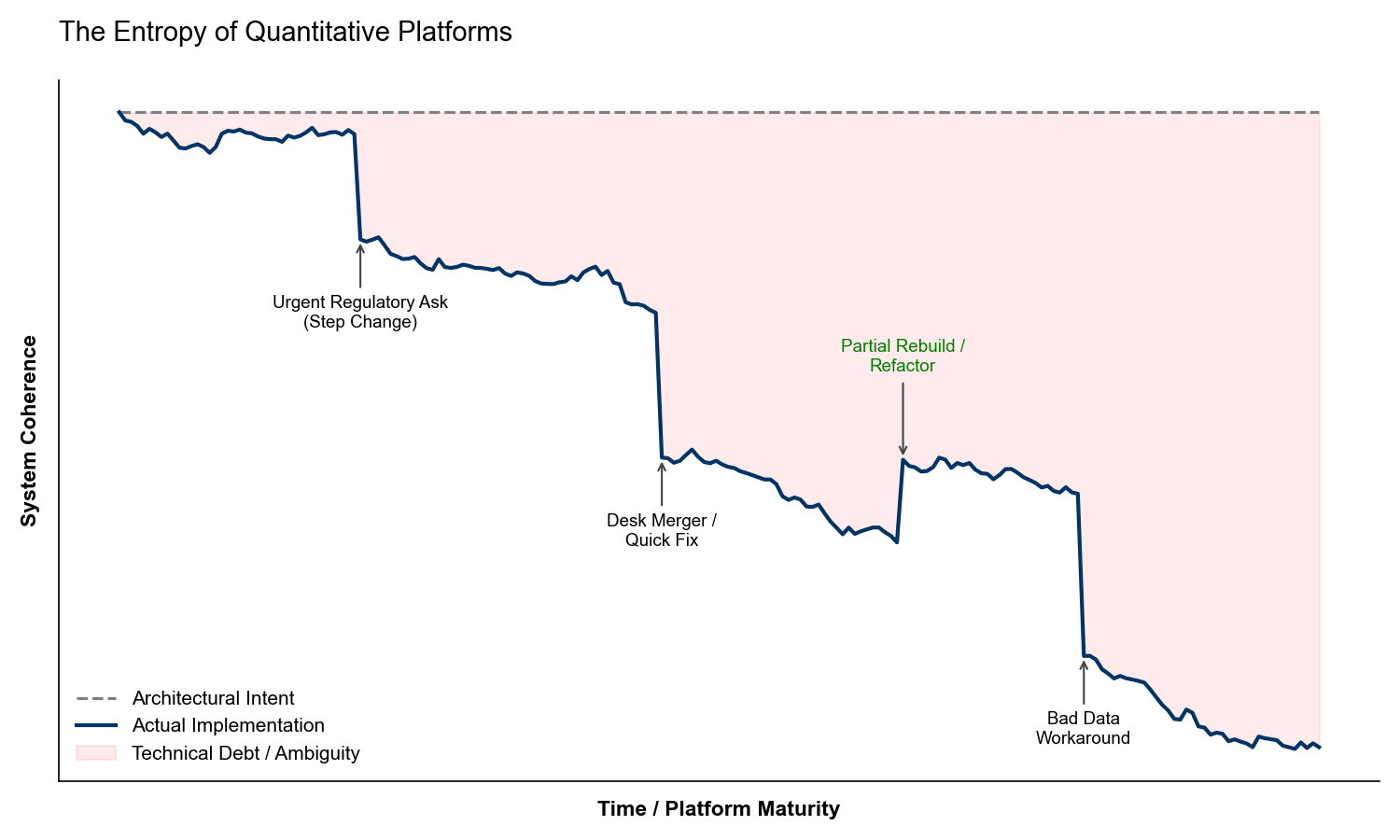

Fig 1. The Entropy of Quantitative Platforms: How ‘Architectural Intent’ diverges from ‘Actual Implementation’ over time.

Fig 1. The Entropy of Quantitative Platforms: How ‘Architectural Intent’ diverges from ‘Actual Implementation’ over time.

In the chart above, each visible drop corresponds not to a single bug or bad model, but to a locally rational decision made under time pressure - a regulatory deadline, a desk consolidation, a production incident - where coherence is traded for immediacy.

Poor Problem Definition and Accidental “Flexibility”

A common starting point is poor problem definition. When objectives are vague or conflicting, architectures tend to become abstract in the name of flexibility.

Flexibility, however, is not neutral by default. There is a meaningful difference between intentional extensibility, designed around known axes of variation, and structural ambiguity where the system defers decisions it will inevitably be forced to make later.

Phrases such as “we’ll decide later” or “this should work for everything” often encode an implicit architectural choice: that contradictions will be resolved downstream, under delivery pressure, or by users themselves. Over time, those deferred decisions harden into behaviour that no longer aligns with any original intent.

This typically enters the system as configuration flags, optional behaviours, or “temporary” abstractions that quietly become contractual once downstream consumers begin to rely on them.

Misaligned Trade-offs Between Accuracy, Performance, and Stability

Another common source of incoherence is the absence of a shared understanding of trade-offs between pricing accuracy, performance, and stability.

These dimensions are not independently optimisable in practice. Improving one almost always constrains the others. In large organisations, different teams optimise different axes based on local incentives: pricing for accuracy, infrastructure for throughput, risk for stability.

When these trade-offs are not made explicit at the platform level, they are made implicitly and inconsistently. The result is not balance, but fragmentation. The platform appears functional, yet its behaviour becomes increasingly difficult to reason about, explain, or trust.

This is why platform debates often feel circular: each group is optimising a different axis, while assuming the trade-off itself is objective rather than contextual.

Data Inconsistency and the Treatment of Time

A particularly insidious class of problems arises from inconsistent handling of reference data, market data, and point-in-time assumptions.

These are often treated as implementation details or data-quality concerns. In reality, they are architectural decisions. A platform that does not treat time consistency as a first-class constraint will inevitably encode multiple, incompatible notions of “now”, “as-of”, or “effective”.

This often surfaces as the “8:00 AM problem”: risk reports that disagree with trader screens because the platform lacks a distinct Start-of-Day (SOD) state. One system sees “Yesterday’s Close,” while another sees “Today’s Open,” but neither correctly accounts for the corporate actions, expiries, and lifecycle events that must mechanically occur between the two.

At first, the numbers will look close enough. Over time, reconciliation effort increases, explanations lengthen, and confidence erodes. By the time discrepancies are visible externally, they are usually deeply embedded.

Why These Are Not Hard Technical Problems

It is tempting to frame these failures as technical shortcomings: insufficient compute, inadequate models, the wrong technology choices.

In practice, these are rarely the limiting factors. None of the issues described above require novel algorithms or exotic tooling to address.

The real difficulty lies in making deliberate choices early, enforcing them consistently, and resisting short-term delivery pressure to bypass the architecture “just this once”.

Most platforms fail organisationally before they fail technically.

The Slow Loss of Coherence

When platforms fail, they rarely do so abruptly. They slowly lose coherence.

Exceptions accumulate faster than they are removed. Temporary workarounds become permanent structure. Edge cases begin to define the core. The system still produces outputs, but the conceptual model that once tied it together erodes.

By the time symptoms are obvious, excessive reconciliation, brittle releases, loss of trust, the causal decisions are often years in the past. Reversal is possible, but expensive, risky, and politically difficult.

At that stage, rebuilds are often framed as technical resets. In reality, they are attempts to restore coherence.

What Rebuilds Reveal

Repeated rebuilds tend to surface the same lessons.

They expose where abstractions leaked, where flexibility became ambiguity, and where implicit assumptions quietly turned into contractual behaviour. Second and third builds are usually less ambitious in surface area and more opinionated in structure.

Paradoxically, maturity often results in less flexibility, not more. Decisions are made earlier, boundaries are clearer, and variation is channelled rather than absorbed indiscriminately.

This is not a reduction in capability. It is an acknowledgement that coherence is a scarce resource.

Architecture as an Ongoing Commitment

No single post can provide an exhaustive explanation of why platforms fail, nor should it try to. The purpose of this piece is to establish a way of thinking about platform design and decay that prioritises explicit trade-offs, engineered differences, and coherence over time.

Platforms do not succeed because they are clever. They succeed because they make deliberate choices, enforce them consistently, and revisit them consciously as objectives evolve.

Most platforms do not break suddenly. They slowly lose coherence.